My mother didn’t approve. When I announced to her that I was planning to quit my good editorial job in New York to attend Columbia University full time – to get a fine education and a B.A. degree in Literature and Writing, a credential that would help qualify me to write a book in my effort to find my missing daughter, my mother was against it. She didn’t understand. My mother and I were cut from different cloth.

“Why don’t you just get married again – while you’re still young and pretty! — and have more children — before it’s too late! — and put the past BEHIND you?” she stressed. “Your daughter, wherever she is, is probably a spoiled brat who doesn’t give a damn about you. You’re ruining your life – and your looks — over this!”

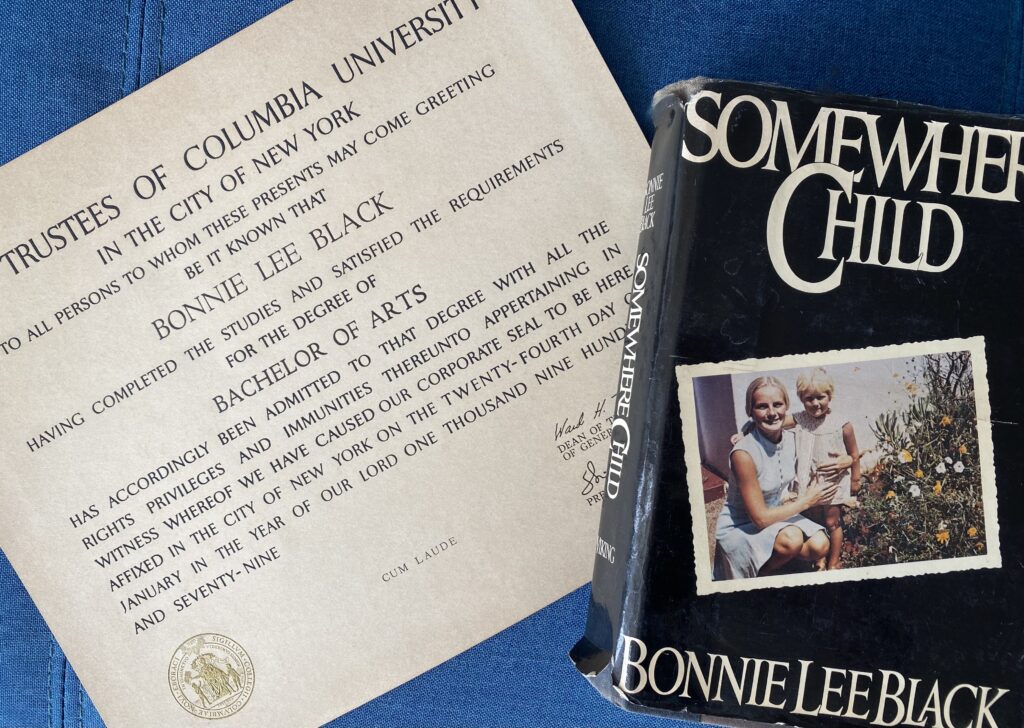

When at the age of thirty I defied my mother to attend Columbia’s School of General Studies on a full scholarship from the Helena Rubenstein Foundation, my mother stopped speaking to me for quite some time. Ultimately, though, after I graduated with honors in January 1979 and wrote the book I’d hoped to write, which was published by Viking Press in October 1981, and I was sent by Viking on a nationwide book tour, my mother was proud of me. I knew she would be.

Toward the end of that book, SOMEWHERE CHILD, I wrote about my experience at Columbia in the third person, as though it all happened to someone else:

She loved Columbia the way she loved snow-capped mountains, star-flecked skies, crashing waves, and African sunsets: distantly and reverentially. She thrilled at the old buildings with their marble staircases worn down by countless students’ shoes, the professors with their esoteric specialties and their messianic drive to share their knowledge, her earnest classmates discussing the protagonists of novels the way doctors might discuss their best cases.

But in most of her classes, she felt ill-equipped and overawed, scrambling to keep up with the lectures, trying to take careful notes, straining to make sense of it all. Often, she felt as if she were an interloper, a gate-crasher at a highbrow cocktail party.

It was only in her creative writing classes that she felt she belonged. There, sitting in dimly lit classrooms at conference tables where they offered up their lives like sacraments on platters of white bond, she and her classmates were comrades, bound by the same neurotic need to write.

And there she was a scientist performing experiments on herself, trying to find the true origin of her problem and the cure for her pain. Why had her life turned out this way? Where had she gone wrong? She probed and examined her past as if it were lying in a petri dish, and then she reported her findings in the form of true stories.

Looking back now, I must say that deciding to attend Columbia University was one of the best life decisions I’ve ever made. It was there that I learned how to stretch my mind as I never otherwise would have, and I learned that I had a voice and a responsibility to use it for good. I was no longer Pretty Little Miss Nobody from Nowheresville, New Jersey, whose highest calling was decorative. I learned I had a good brain, and, as a thinking, caring person, I had value. Columbia forever altered my life’s tragectory, and I will be eternally grateful.

But now, today, as I read and watch the news of the current turmoil on the Columbia campus, my heart aches. As an alumna, I receive email updates from the administration (as if I were a big deal donor, which I’m not), justifying their actions in calling in the police (dressed in riot gear, no less) to quell the students’ Pro-Palestinian demonstrations and encampments, which have sparked similar protests on university campuses all over the country.

I actually feel sorry for Columbia’s President Shafik; she’s no doubt caught between a rock and a hard place, between Money (the students are demanding that Columbia divest its financial interests in Israel) and Morality (the students are standing up against the Israeli government’s genocide in Gaza). Shafik, I imagine, is a realist and as such she knows that in the United States Money wins nine-tenths of the time. Also, she probably doesn’t want to lose her job.

But my heart is with those Columbia students and the faculty members who support them. I admire their bravery, their willingness to take a stand and speak out and even be arrested for doing so. By any measure, Netanyahu’s ongoing war and the incessant bombing of innocent civilians in Gaza is WRONG, unconscionable, indefenceable. And it is not antisemetic to say so. In fact, a large number of the student demonstrators and faculty participating in these Columbia protests are Jewish, and they make clear that standing up for what is right and moral is in the highest Jewish tradition, which those of us who are non-Jews have always admired.

In my view – and it was at Columbia where I learned, at last, in my early thirties, that my point of view is as valid as anyone’s, and I have a right to express it – the Columbia students have already succeeded mightily in helping to raise awareness all over the U.S., and maybe even the world, of what’s happening in Gaza and how wrong it is. But will their demands for divestment and a total ceasefire win out? If I were young like them and still idealistic and hopeful, I’d say, Yes, maybe they will!

But I’m afraid I know better now. As a Columbia Business School grad once told me flatly, “In the U.S. we adhere to the Golden Rule: He who’s got the gold makes the rules.” Yes, this seems to be the case. At this age and stage, nearing eighty and worldly wise, I fear that Money will win in this struggle too, as it almost always does. And that’s why my heart is breaking.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~